Ever since checking out Headlander at E3, I’ve been on the lookout for its official release. At the show, Double Fine’s quirky take on the Metroid formula proved to be a fun concept in demo form. After finishing the full game, it’s safe to say that even with its share of problems, Headlander isn’t merely a clone of Nintendo’s past glories. It carries enough personality and unique gameplay to set itself apart in the extremely crowded retro-inspired genre that so many videogames tend to fall nowadays.

Headlander tells the story about the last surviving human aboard a derelict ship drifting aimlessly in space, who’s awoken by a mysterious voice. Sadly for him or her (you get to pick the gender of your protagonist), they can’t reply. After all, they’re just a head encased in a rocket-propelled helmet, lungs not included. A true silent protagonist. The main gist of the game then is landing on increasingly more useful robot bodies as you explore the ship, make your escape and find out just what went wrong in this dystopic version of a 1970s sci-fi future where humans have given up their organic bodies for the promise of eternal life as sentient robots.

Even though the game is fairly short, clocking in at around four hours, depending on how set you are in following the main story path, Headlander manages to punch in all the correct buttons that make a Metroid inspired game. That is, exploring a map, discovering an obstruction that requires a certain ability, or in Headlander‘s case, a different color-coded door, and then finding the correct robot to suck the head out of and landing. Thankfully, Headlander doesn’t stop there, and while yes, for most of it you’ll be on the lookout for colors ranging down the chromatic scale to open increasingly more demanding doors, from yellow down to purple, there’s a fair share of secrets and extras to find.

The upgrades you discover mostly serve to build upon the core powers your helmet provides you while you’re floating around, like shields and boosting power, but there are other benefits tied to the bodies you take over. For instance, one of these upgrades allows you to program drones that can help you during fire fights. The catch is that very few of these pickups are actually required to finish the story progression. In fact, the game is very open to the idea of having you complete it with just about whatever amount of upgrades as you want, aside from two or three essential items that you bump into quite easily.

That also goes for the points that you pick up along the way, which can be put into further powering up your helmet and abilities. During the course of my playthrough, for instance, around half way through the game, I decided to explore more of the map in search of these upgrades, but not because I felt the game was particularly difficult. I wanted to find out just how powerful my Billy Dee Williams lookalike could become, and boy, I totally did.

If you just happen to explore every nook and cranny throughout Headlander, there’s a point you’ll get to where it won’t matter how strong of a body you manage to find and take for your own. Your head will be fast as a bullet and just as deadly to anything it comes in contact with, except doors, as you’ll always need a body for those. It’s a dramatic shift in difficulty that makes even the last boss fight trivial, let alone any other combat scenario.

And while the Headlander‘s aim isn’t pointed towards challenge, it’s a little jarring that out of the two boss fights in the entire game, the first is remarkably more involved and complex than what awaits you at the end. The entire lead up to that encounter is based on a mildly amusing concept: a turf war wrapped by a thin crust of chess. Very few of the actual rules of that game are followed, per se, but the overall idea is carried over at least in a personable way, with two teams and opposing units fighting one another. The boss fight itself is more or less a culmination of every mechanic seen in the previous encounter, and even if you’re not in the same overpowered state I was at the time, it’s far from being troublesome once you figure out its patterns – a nice knot to the game’s best section, by far.

Under Headlander‘s layer of gameplay lies a funny script, which as customary of Double Fine, pokes fun at the ridiculousness of the game’s setting and characters. The voice acting is particularly noteworthy, thanks to returning talent from Double Fine’s earlier games, like Richard Steven Horvitz, who played Raz in Psychonauts and lends his voice to MAPPY, a happy go lucky robot who sadly meets its demise multiple times throughout your adventure. The game also includes a host of references to pop culture that will probably make you chuckle at some point, or at least go “ah, I know what they’re alluding to”. The plot, however, is fairly predictable, if not a little underwhelming, especially towards the end. It builds up to a climatic finale that never really happens.

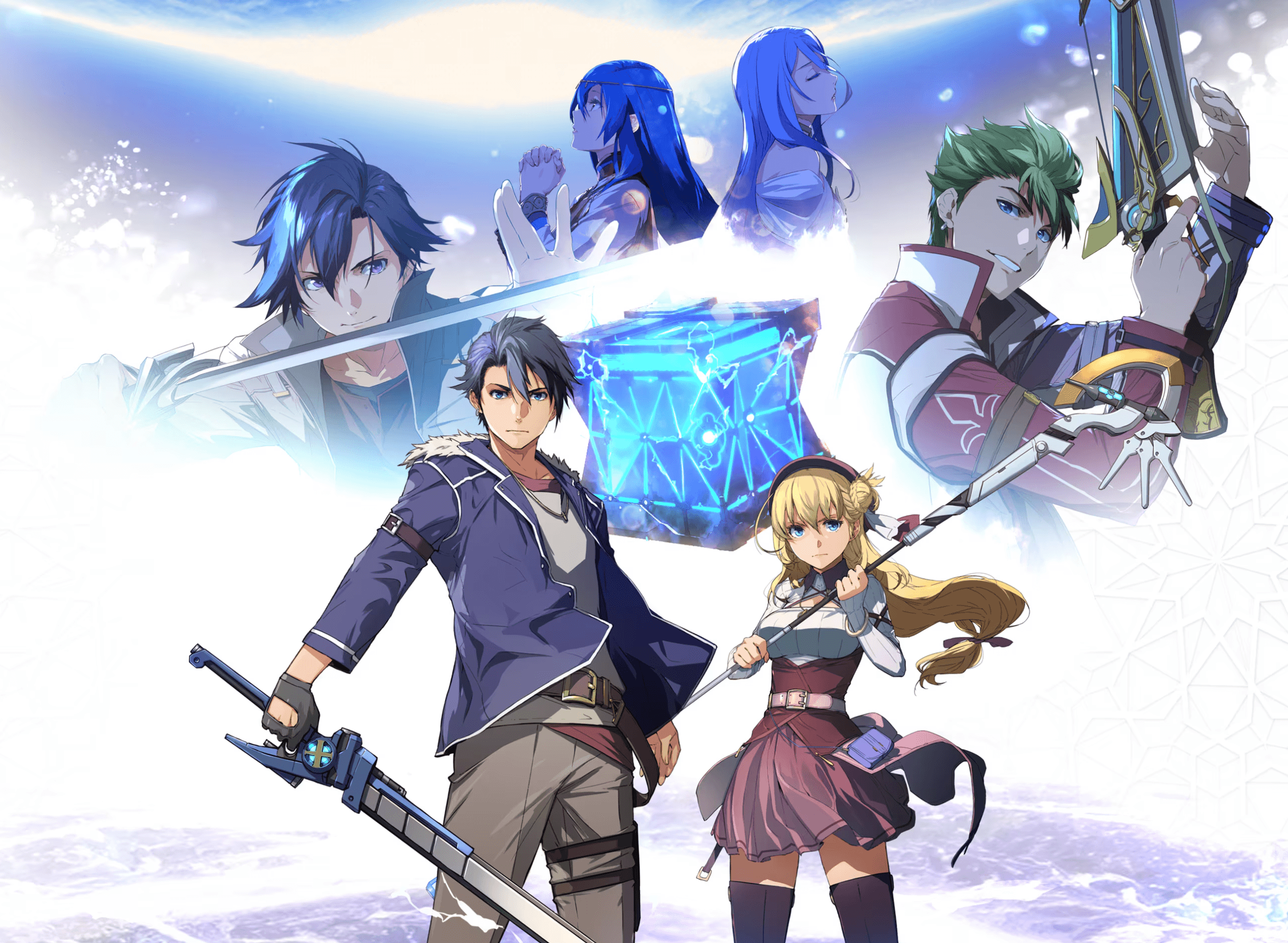

Thanks to the sheer amount of charm its presentation manages to convey through its beautifully retro menus, world and character designs, Headlander‘s isn’t exactly a throwaway and forgettable game. Even in its short run, Headlander varies visually at a brisk pace, throwing beautiful vistas for you to run across, as well as indoor sections that require a bit more thinking than just holding right on the analog stick. It’s just missing a certain oomph that its inspiration had.