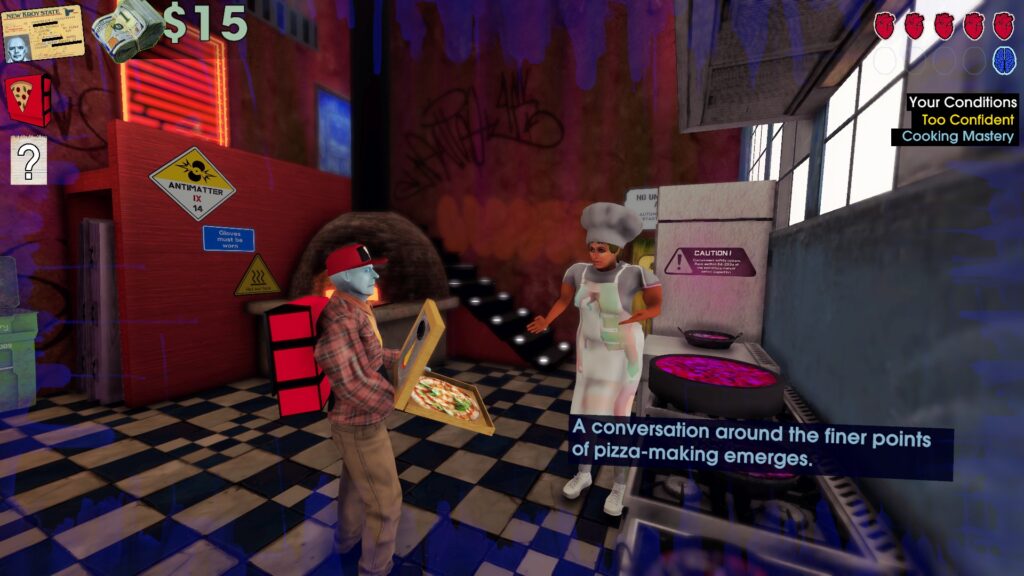

My first playthrough of Betrayal At Club Low ended in failure after unsuccessfully trying to convince a bartender I knew a thing or two about mixing drinks, at which point I lost my nerve and had to leave. This was after I spent almost 30 minutes trying to get into the club in the first place by trying to sneak in the back door, attempting to use the fire escape, and trying to convince the bouncer I had a pizza to deliver to the DJ (which eventually did work).

My second playthrough was far more eventful – and often successful! – but eventually spun out of control in spectacular fashion. Over the course of an hour, I had taken over for the chef and made a horrible stew, talked the DJ into leaving after revealing the shitty deal his agent had been giving him and then took his place, spinning a tune so poignant it moved the dancefloor to tears; I convinced a security guard I was actually an IT person moonlighting as a pizza delivery guy after failing to knock him unconscious just moments before, got on the good side of a mobster despite having stolen his jacket, and then ultimately failed to make my escape after all was said and done.

It was a wild night.

Betrayal At Club Low is a riot. Every moment is a series of increasingly absurd situations that only get better. Developed by Cosmo D, known for their work on the Off-Peak series and The Norwood Suite, Betrayal At Club Low pitches itself as a “bespoke tabletop session.” As such, it’s a game that borrows heavily from modern tabletop RPGs in how it handles dice rolls and the resulting outcomes, using it as a launchpad for the game’s particular brand of absurdity.

You take on the role of a secret agent on a rescue mission to extract a fellow agent from a nightclub (the titular Club Low), as they are believed to be held hostage there. Your cover story is that of a pizza delivery person. Everything past that — how to get in and how to extract your target — is up to you to figure out. As this is a game of dice rolls, that means having to be flexible and prepare for a lot of failure. Not in the “game over” sense, mind (though that is very much a concern as well), but in how things will seldom work out how you want them to.

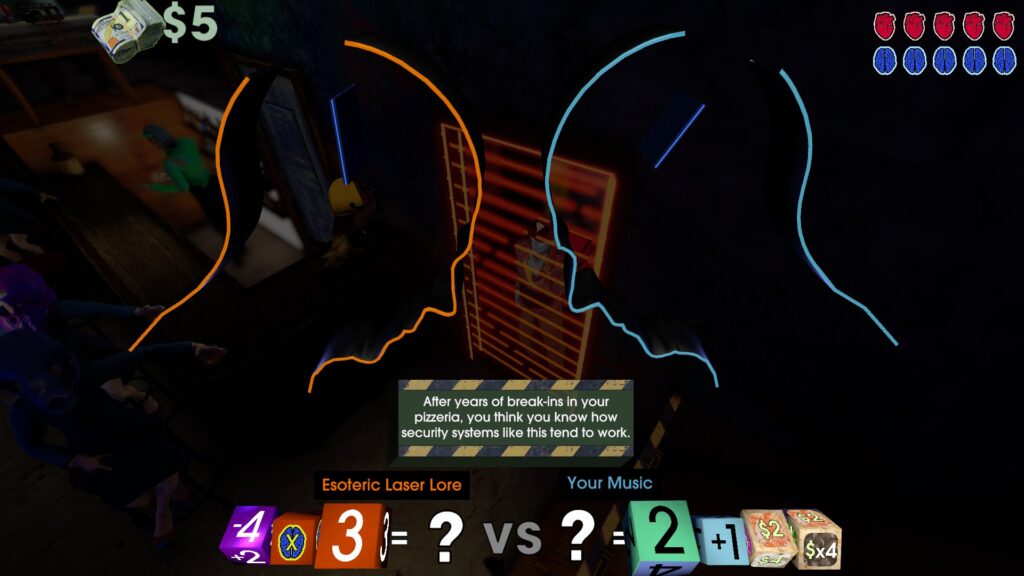

Like many modern tabletop RPGs, Betrayal At Club Low approaches success and failure not as a binary state (you either fully succeed or fail) but rather one with more nuance. There are three basic results: a full success, wherein the number you roll is greater than that of your opponent, an even result, where both of you end up with the same number, and a complete failure, where you end up with the lower number. A full success, obviously, gives you the desired outcome with no drawbacks and often some nice bonuses. An even one will still succeed, but it’s likely going to include a negative condition (conditions basically add extra dice you’ll have to roll) on top of whatever positive one you earned as well. And an outright failure just applies negative conditions.

In almost all cases, a failed roll just means taking a negative condition that will clear after your next roll. At worst, it means the person you’re dealing with will take a condition that will make their dice stronger. Either way, you’re rarely locked out of trying again as many times as you like unless explicitly stated otherwise. The catch is that not all conditions, positive or negative, are strictly good or bad. Some of them are more a mix where the dice you get can help as much as it can harm, such as one where half the faces will reduce the number you roll and the other half will increase it, making them useful to have despite the inherent risks.

There are ways to influence the dice in your favor, of course. Each roll is dictated by a particular stat. Each stat acts as a separate dice that you can upgrade to increase their strength, either one side at a time or all of them at once. These stats range from standard fare abilities like physique, deception, wit, wisdom, and observation, to more peculiar types such as music or cooking. Which ones you choose to invest in determine your approach to most situations but by no means lock you into anything.

You can also re-roll any of your dice a couple of times before you’re locked in, allowing you a chance to turn a bad roll around. There’s also your pizza dice. Pizza dice are fully customizable. Each face of the die can be given different effects, ranging from increased tips (you are a pizza delivery person, after all) and multipliers for said tips, restore lost health and nerve (if either reaches zero, it’s game over), and the ability to re-roll one or more of the opponent’s dice or swap your main dice with theirs. It’s still ultimately up to chance whether those effects will trigger when you really need them to, but they’re very existence is enough to keep each roll exciting for the mere chance a complete turnaround can happen, for good or bad.

It all serves to make you just go with the flow and see where the game goes instead of constantly reloading saves until you get the ideal result. Like actual tabletop games, it’s more fun when things go awry than exactly according to plan, especially if you can then suddenly turn things around at a crucial moment. It allows Betrayal At Club Low‘s comedy chops to really shine, as it thrives off the chaos that dice rolls can create in determining the course of the story.

A great example: Remember how I mentioned I successfully tricked a security guard into thinking I was IT after failing to knock him out? There’s a bit more to it. After he bought the lie, he gave me the password to the security terminal before literally rocketing off to a bar to watch his tennis game. I immediately went to use it and — surprise! — it was a fake code. The computer proceeded to blast “eye-searing beams of light” at me. I tried to avoid it, but failed. So I was able to successfully gain access to the security room and get rid of the guard, but now I was dazed and injured and didn’t have access to the terminal. The odds in any future rolls were heavily stacked against me now. The fact that this all happened after I “convinced” the guard I was actually IT is what makes this whole thing work. Clearly the guy didn’t actually believe the lie: he was just looking for an excuse to clock out early and watch his tennis game at the bar and let the computer sort things out.

In another: one of the very first rolls you make has you deciding what to do about a sudden stench from the city’s failing infrastructure that engulfs you on your way to the club. You have three options, each using a different skill: try to withstand it (physique), attempt to recognize the scents (cooking), or just accept the situation (wisdom). The result remains mostly the same regardless of which roll you try (if you succeed, you’ll get a positive and negative condition applied), but the choice of roll is fun and establishes the game’s tone perfectly.

It also creates character. Your choice may not ultimately change anything, but it lets you fill in who your character is. If I choose to use my cooking skill there, they actually pick up on very specific smells (tar, coffee grounds, seaweed, and a hint of sherbert?) and conclude that they’ve “still got it.” The conclusion there being that they clearly have a strong interest in food (maybe even experience as a chef outside of their job as a secret agent). It doesn’t ultimately mean anything in the grand scheme, but it helps evoke the feeling of embodying a character in a tabletop game in how your skills suggest a certain background that influences their approach to problem solving.

The player character is mostly a blank slate to be filled in by your actions, much the same way any tabletop characters are mostly just a pitch until the people playing them begin to actually play and see how their characters develop. Though Betrayal At Club Low isn’t nearly working in the same space (such are the limits of a videogame and the parameters of how much choice you ultimately have versus the freedom of live, improvised play), it helps sell the pitch of evoking a tabletop session.

Betrayal At Club Low‘s humor may be one of its draws, but the way it plays with dice rolls and captures the sensibilities of tabletop games is what makes it shine. The myriad ways any one playthrough can go – or a single roll even – make it a joy to constantly revisit and see what happens if you try this instead of that. This is my first experience with a Cosmo D game (I’ve meant to play Off-Peak for ages but haven’t because I’m terrible) and I feel like a fool for putting them off for so long. If this is just a peek at what the stories of Off-Peak City has to offer, I’m very excited to see what else this surreal world has in store.