As I prepared to head to court and present my case for who committed the “crime to end all crimes,” I was confident I had a clear picture of what went down. I’d been as thorough as I could be, chasing down every possible lead, tracking down every piece of evidence and testimony I could. I had a plan and was ready to go. All I had to do now was prove it – and hope I got everything right.

Most murder mysteries are simple and straightforward. No matter how outlandish or seemingly impossible the circumstances, there’s always a singular answer. You just have to find it. Paradise Killer isn’t so simple. Here the truth isn’t something you have to find so much as it is something you have to create.

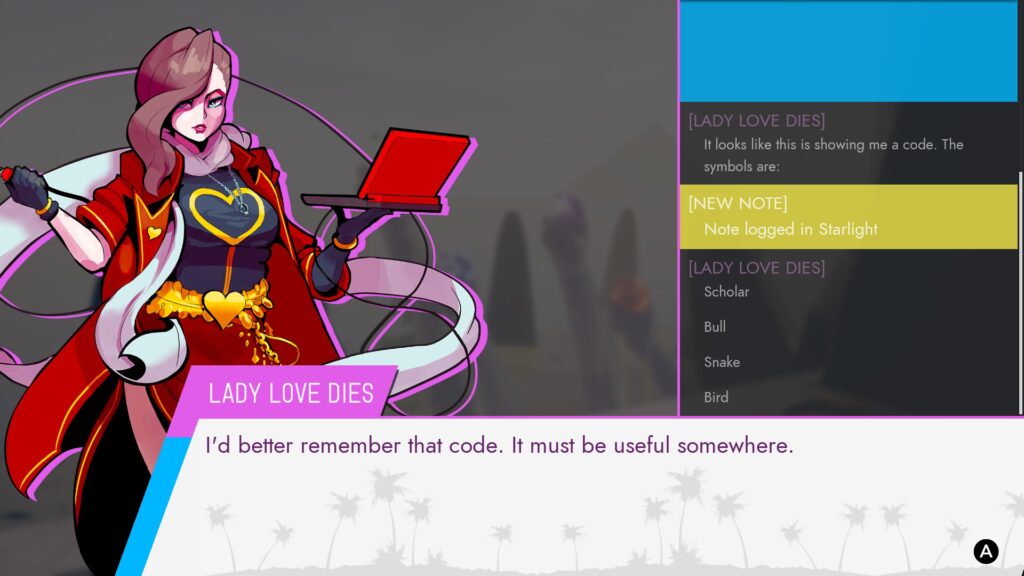

On the final night of Sequence 24 of Paradise Island, a murder occurs. The Council – leaders of the Syndicate, the organization that runs Paradise Island – is dead. Most of the island’s population has already been moved to the next island sequence, those who remain being the prime suspects. Due to the severity of the crime – The Crime to End All Crimes, they call it – Lady Love Dies, the Syndicate’s lead investigator, who’s resided in exile for the past three million days, is brought in to figure out what went down. You do this by chasing down leads, examining crime scenes, and questioning suspects. Paradise Killer is a mix of open world traversal and visual novel-style conversations. An odd mix, certainly, but one that comes together marvelously.

The conceit of Paradise Killer isn’t so much that you’re trying to find the actual truth of the case, but rather find what you believe to be the truth. Obviously puzzling out the actual truth of the matter is ideal, but the game never explicitly guides you toward that answer, nor does it ever tell you whether you got everything – or anything, for that matter – right. All it does is merely point you in the direction of leads and lets you take care of the rest.

Paradise Killer’s pitch is best illustrated by the “official” account of events. Before Lady Love Dies is brought in, the case is already “solved.” A culprit has already been detained and a story put forward by the cops to explain what happened. The long and short of it: a demon-possessed citizen named Henry Division who’s been locked up for the past several years broke free the night of the murder and assassinated the council. Why? Who knows. Demons attack Paradise Island a lot as is, so perhaps this one had a particular grudge against the council. A pretty open and shut case according to the official story. But of course, that’s just one interpretation of the events. Whether it’s really the truth or just a carefully crafted lie is partially what you’re here to uncover.

Like any good murder mystery, your investigation reveals just how suspicious everyone is. Everyone has a possible motive. Everyone has holes in their alibis (if they even have one). Everyone has some bit of evidence that incriminates them. The pieces are there to figure out what could be the canonical truth (whatever that may be), but you never know whether you truly got it. No one is outright going to confess even if you have irrefutable evidence against them. Whatever testimony they give could be truthful just as much it could be pure fabrication, likewise their musings on who they think could be the culprit. Who’s to say? The facts suggest many things and implicate many suspects. Sure, there are key pieces of evidence that undeniably point to someone, but without a clear picture to connect everything together, it’s hard to say what the actual truth is given how numerous and complex the many facts of the case are.

Which is what makes Paradise Killer understand investigation better than many other games. It knows that the process isn’t about solving an intricate puzzle, but rather one of informed guesswork and convincing arguments. If they happen to align with the actual truth, great! Well done! If not, well… it’s no secret that justice is malleable. As long as you find a satisfactory answer that you can make a compelling case for, does the actual truth really matter? Again, Paradise Killer never tells you whether you got everything “right.”

For the entirety of my playthrough I was regularly seconding guessing myself. I had an initial list of suspects that I was certain were guilty in some form. But even then, I had to wonder whether my suspicions had any actual basis. I could make a strong case for, while others had little in the way of definitive evidence. Likewise, people I thought were likely innocent regularly tested my belief in them as there was just enough suspicion to raise some measure of doubt against them. Like Paradise Killer constantly reminded me, the facts and the truth are very different things, and just because I had evidence that could point to someone didn’t necessarily mean they were the culprit, and vice versa.

Once you think you’ve done enough investigating, it’s time to head to court to present your case. The way court plays out is straightforward: the judge goes over each step of the crime and asks you who you think is responsible. You have to choose who to accuse of each crime, in other words. It’s not just a matter of answering who committed the murder, but who was responsible for all the steps that lead to it. How did Henry escape? Did he do it himself or did someone help? How did the culprit get past all the security protecting the council? Was it just one person or were multiple people involved? It’s here that the game’s constant talk about “finding your own truth” becomes clear as there’s no singular answer to any of these questions. There are always multiple people who can be reasonably accused. You just have to decide who.

Going into court, I thought I had a clear idea of who was guilty of what. I was confident in my answers and ready to move forward with them. But when faced with all the possibilities, I had to stop and really think everything through. Who did I want to pin each crime on? Which of these suspects was really responsible? The easy choice would be whoever had the most evidence against them, since it would be a cinch to make a convincing argument. But the easy choice isn’t always the right choice. Just because I had less evidence on someone didn’t necessarily mean I couldn’t make a good argument, after all.

It’s tricky because, as much as I was certain I had a clear grasp on how everything went down, once I had to start putting together the truth I wanted to present, things didn’t feel so straightforward anymore. The entirety of the case is complex. I had so many probable suspects in front of me, many of whom were obviously guilty and could easily be proven as such, that I had to very carefully consider what sort of story I wanted to put forward based on the facts in front of me. I knew there were certain suspects I wanted to take down but getting there was the tricky part. Was a straight accusation enough? Or did I need to build a link between other crimes and suspects to better establish someone’s guilt? It’s a difficult dilemma.

In the end, I did successfully get everyone who I knew were guilty. Got the confessions and everything. It all wrapped it pretty nicely, all told. Wasn’t entirely sure whether I took the best route to get there, but… what’s done is done. With a case as messy as Paradise Killer’s, I don’t there’s any one ideal solution. All you can do is trust your judgment and hope for the best.