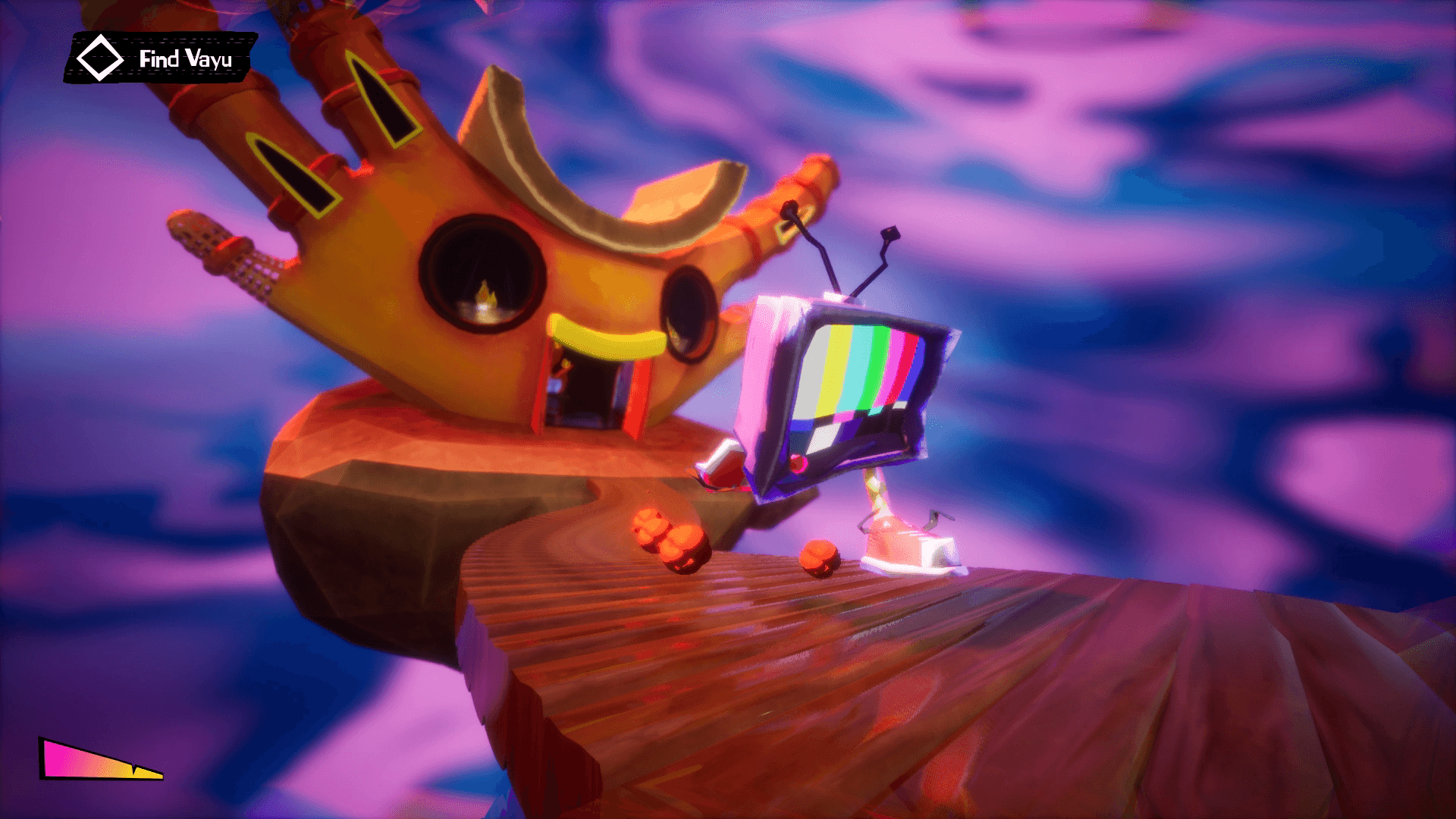

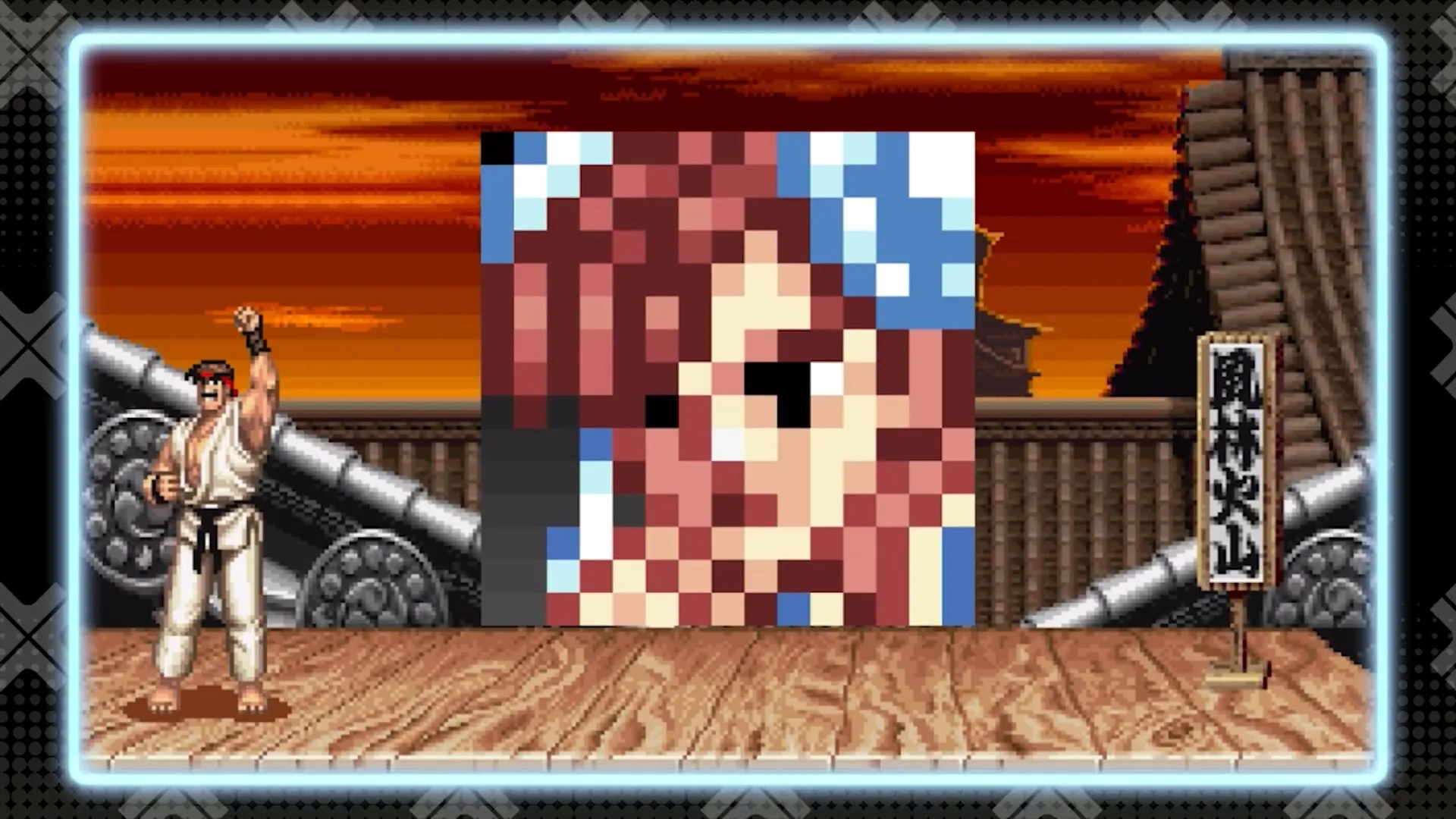

1000 Deaths is surreal. It’s a platformer where you play as a CRT television running through psychedelic levels in service of helping a few individuals make major decisions across their lives to see what could have been. Specifically, it’s a speedrunner platformer (if you want it to be; that’s entirely optional) wrapped around a series of stories that deal in the human condition.

1000 Deaths follows a group of friends – Vayu, Maxie, Terry, and Boga – and the numerous paths their lives could take, starting from childhood all the way through to their deaths. It all begins when Vayu, nearing the end of a long life, feels regret over not having lived to their fullest. What if instead of staying in their hometown fixing and tinkering with electronics all day they had followed their best friend to chase fame and fortune in Jollywood? What if they had run for mayor of their hometown? They’ve been working on a project that would allow them to answer these questions and more, a TV that can move between different timelines to see what other possibilities exist at each major junction of their lives.

Your role in all this is to help them make these decisions. By diving into their headspaces and viewing their innermost thoughts you see the potential outcomes of each path (or the idealized outcomes as the case may be) and guide them toward which one to take. It’s always a choice between two possibilities. Each is unlocked by playing a series of quick levels where you, as the TV, navigate obstacles and disorienting gravity to catch glimpses of their past and future. Each level sees you trying to reach or unlock the exit. Sometimes that’s as easy as just moving forward, other times you need to unlock it by collecting discs or merely collecting a number of green CRT sets scattered around the level.

The levels are designed for speedrunning, the TV having just enough movement options to allow you to cover ground very fast thanks to a makeshift jetpack attached to their back. On my first pass through a level I would just focus on getting through because they are no joke. 1000 Deaths strikes a balance between levels that are difficult because of obstacles (fireballs usually) and those that are hard because of navigating the wild gravity at play. When you move along a sloped or rounded surface, you remain attached to the platform rather than fall off. It’s only actual ledges that make you plummet into the void below. Jumping, crucially, doesn’t keep you affixed to the orbit of whatever object you were standing on. Helpful in most cases, but downright devious when you need to carefully navigate rotation platforms to get to the underside of something to reach the exit.

Finding shortcuts and figuring out the routing for each level is a thrilling challenge. The few levels I made a proper effort to learn and speedrun were largely simple in appearance, but hitting the medal times took work. It exposes the finesse of the mechanics and the cleverness of the level design. Some stages I could look at and immediately see time saves (albeit ones that still required some very fine and swift movement to do), while others would be hidden well after dozens of attempts. It does what you always want out of a speedrunning platformer: levels that you can spend countless hours optimizing, slowly unfurling how the dev times were able to be so low.

Movement can be fiddly sometimes due to how some abilities are mapped. Namely the boost jump. Pressing jump and dash at the same time while not moving will give you a higher jump, which is key at clearing certain obstacles, but it’s very easy to be just barely off on pressing the two buttons simultaneously and get either a forward dash or a jump into an air dash. Supremely frustrating.

But the headspaces and the platforming levels are only half of the game. The other half places you in moments in time following each of the main characters. These scenes act as context for each junction point in their lives, allowing you to roam about and see what’s happening in the real world and learn about the cast. They’re also more easygoing platforming hubs you can explore and play around in at your leisure. They’re very brief sequences, used primarily as a vehicle for delivering the story of the cast’s lives.

Vayu’s predicament is one of deciding whether to stay in their hometown or follow their best friend in chasing fame and fortune. Terry wants to create a new “superfood” and become wealthy by doing so, no matter what it takes, which leads to a choice of how far they’re willing to go, whether there is actually a cost too great or not. Boga is interested in inventing toys, but is torn on whether to do so alone or in cooperation with their friends. And Maxie is confronted with their noncommittal nature when one of their bandmates expresses their love for Maxie. The cast makes appearances in each other’s stories in various roles, illustrating how no matter the wildly different paths they take, they all always end up somewhere within each other’s orbit.

Vayu’s story is the first you play through, deciding a new course for their adult life. Staying is appealing because Nowherestown is all they’ve known and they’re comfortable working at the electronics repair shop. It’s a simple life, but one they’re content with. To leave that all behind for the unknown is understandably anxiety inducing. Staying in this case would lead them to run for mayor to try making the humble town a better, more prosperous place. But they also long for adventure, an escape from the doldrums of small town life for something new and exciting. Following their best friend Maxie to take their shot at fame could be just what they’re looking for.

On my first pass I chose to let them leave with their friend. The whole point of this exercise was to explore other possibilities, right? What better way to start than by taking a big leap. The result jumped forward by ten years and saw the two barely scraping by in a shitty apartment. Vayu works a job they hate while Maxie lays about all day occasionally taking on gigs (that often don’t pay) trying to make it as a performer. A far cry from the comforts and stability of home. Vayu and Maxie are still friends, but it’s obvious Vayu is growing resentful. On a later pass, I chose to have Vayu stay home and run for mayor. Immediately things seemed much better for the two of them. Vayu’s run a successful campaign and Maxie has become a bona fide rock star.

Both routes add some extra complications that lead to further decisions — a moral dilemma in one and the fraught realities of being a politician in the other — but they all inevitably end in the premature death of one of the protagonists in some comical fashion. 1000 Deaths generally leans on the lighthearted side. It’s surreal, often absurd depiction of everyday life and the relatable struggles the cast endures finds plenty of levity, even moments that are frank and resonate. It’s often very silly, but it still manages to be very sincere. The stories can’t be too involved due to the limited space they work with — each route from start to finish lasts roughly a dozen or so minutes apiece not counting the platforming segments — which forces them to be very efficient, but 1000 Deaths works within those limitations well.

On some level I wish there were more because I like the cast and would have loved to see more of them. But 1000 Deaths‘ lean narrative is also one of its strengths. It’s a fun break from the gauntlet of platforming challenges and texture to the overall experience. I love a good speedrunning platformer and 1000 Deaths fulfills that role with ease, despite the occasional frustration with the control mapping of some of the abilities. But one that also has good narrative hooks in it is even better.

Callum Rakestraw (he/him) is the Reviews Editor at Entertainium. You can find him on Bluesky, Mastodon, and his blog.