In Chicago, the arrival of Prohibition opened a lucrative new market to the city’s various criminal factions in January 1920. No longer limited to prostitution and gambling, the mobs built empires of illegal production and distribution of alcohol. The profit at stake brought the gangs into violent conflicts, and grisly events like the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre of 1929 made Chicago synonymous with organised crime. Making a permanent mark on culture, this period has inspired books, films, and a number of games – a list to which we can add Empire of Sin.

Developed by Romero Games – fronted by industry veterans and husband-and-wife team John and Brenda Romero – Empire of Sin is not the first strategy game with a 1920s Chicago theme, but may be the most ambitious. At the outset of the game, the player chooses one of 14 distinct bosses, who are a mixture of real and fictional figures. Having done so, they are tasked with nothing less than building a criminal empire, amassing a fortune, and eliminating rivals to become the undisputed kingpin of the Windy City.

The overarching grand strategy component is just one of four distinct aspects to Empire of Sin. Building an empire means acquiring numerous rackets like speakeasies, breweries and brothels which are maintained through an economic management layer. Moving their boss and other gangsters around the city, the player will meet new characters and begin missions which form the core of a role-playing element. Finally, Chicago is a violent place and the various battles with rival factions, non-aligned thugs, and the police play out in the form of turn-based tactical battles.

Any one of these sets of mechanics could be used as the basis for a game in and of itself. By combining them, Romero Games set themselves a daunting task. Empire of Sin has a sprawling, almost overwhelming design that brims with possibilities. Unfortunately, like a rookie mobster, the developers have grabbed control of more territory than they can keep under control. The more elements a game has, the harder it is to make each one reach its potential and Empire of Sin is what Brenda Romero calls a “system soup”. The attempt to fuse grand strategy, management, role-playing and combat is admirable but each component competes with the others for space in the design and each one ultimately feels shallow.

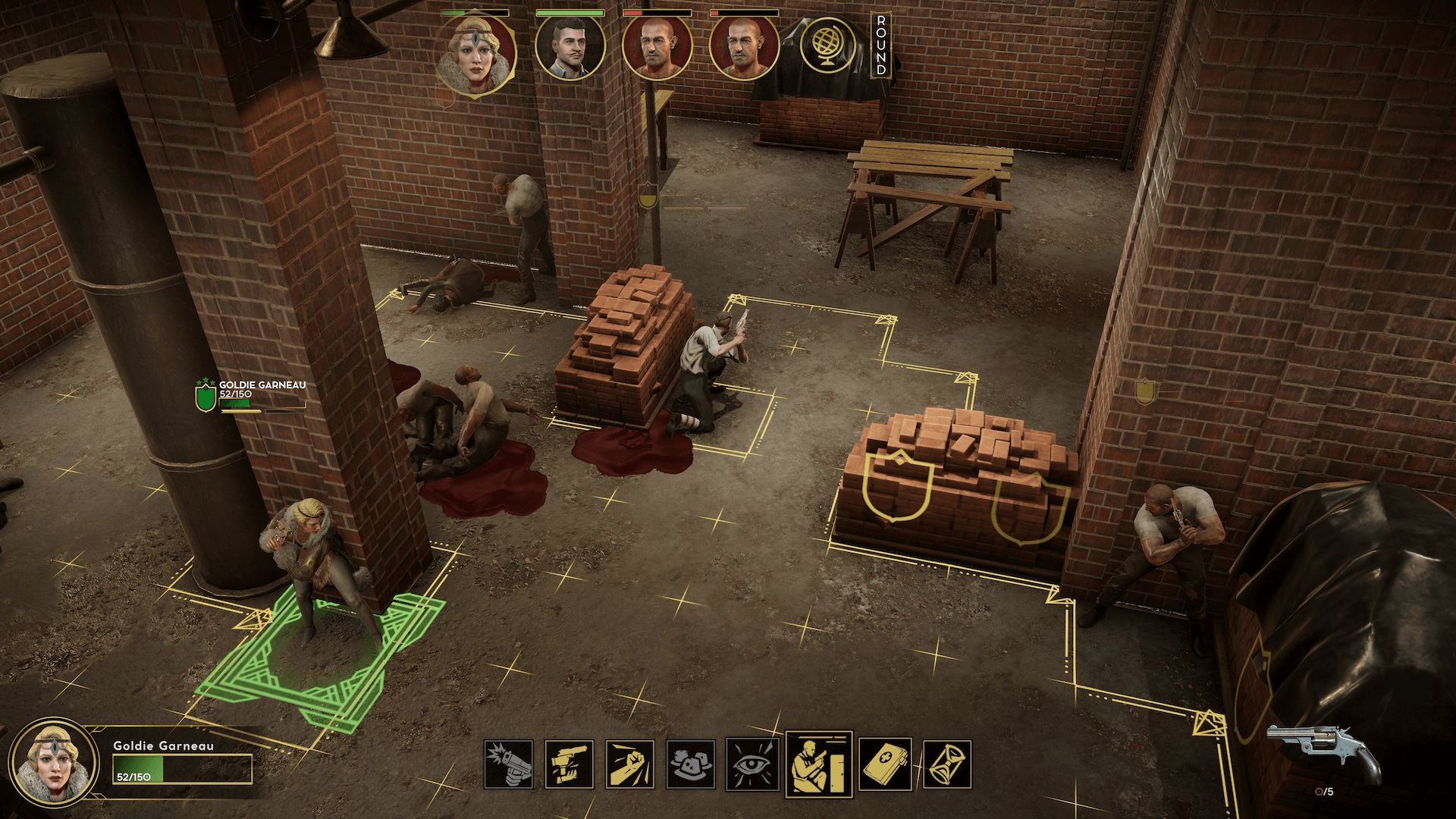

Take the combat, for example. Romero Games have lifted the combat system almost directly from the XCOM series, which is difficult to argue with given how tried-and-tested said system is. The reality is, however, that battles in 1920s Chicago are nothing like as exciting as the ones on an ADVENT-controlled future Earth. For one thing, the variety of combat environments is seriously lacking: fighting within a brothel is almost identical to fighting in a brewery, or even to a shootout that takes place in the street. Victory usually depends on using a handful of familiar abilities repeatedly. Empire of Sin expects players to undertake dozens, maybe hundreds, of these identikit engagements which barely change over hours of play. Worse, there’s no way to auto-resolve battles. This becomes a real sticking point when war breaks out, and every trivial skirmish has to be played out in full, one after another.

As opposed to XCOM’s randomly-generated but customisable soldiers, Empire of Sin has no less than 60 pre-built gangster characters. This is another key example of the game’s emphasis on quantity over quality. Yes, these mobsters have their own special quests and unique sets of traits: but they’re flat, uninteresting and have little in the way of personality. They aren’t promoted through combat, but instead gain new abilities at timed intervals. This means that upgrades to their effectiveness don’t come from hard-fought successes in the streets, but are inevitable with the passing of time. Empire of Sin is an open-ended game in which players are invited to tell their own stories, but it’s difficult to bond with characters who change in such a rigid, predictable way.

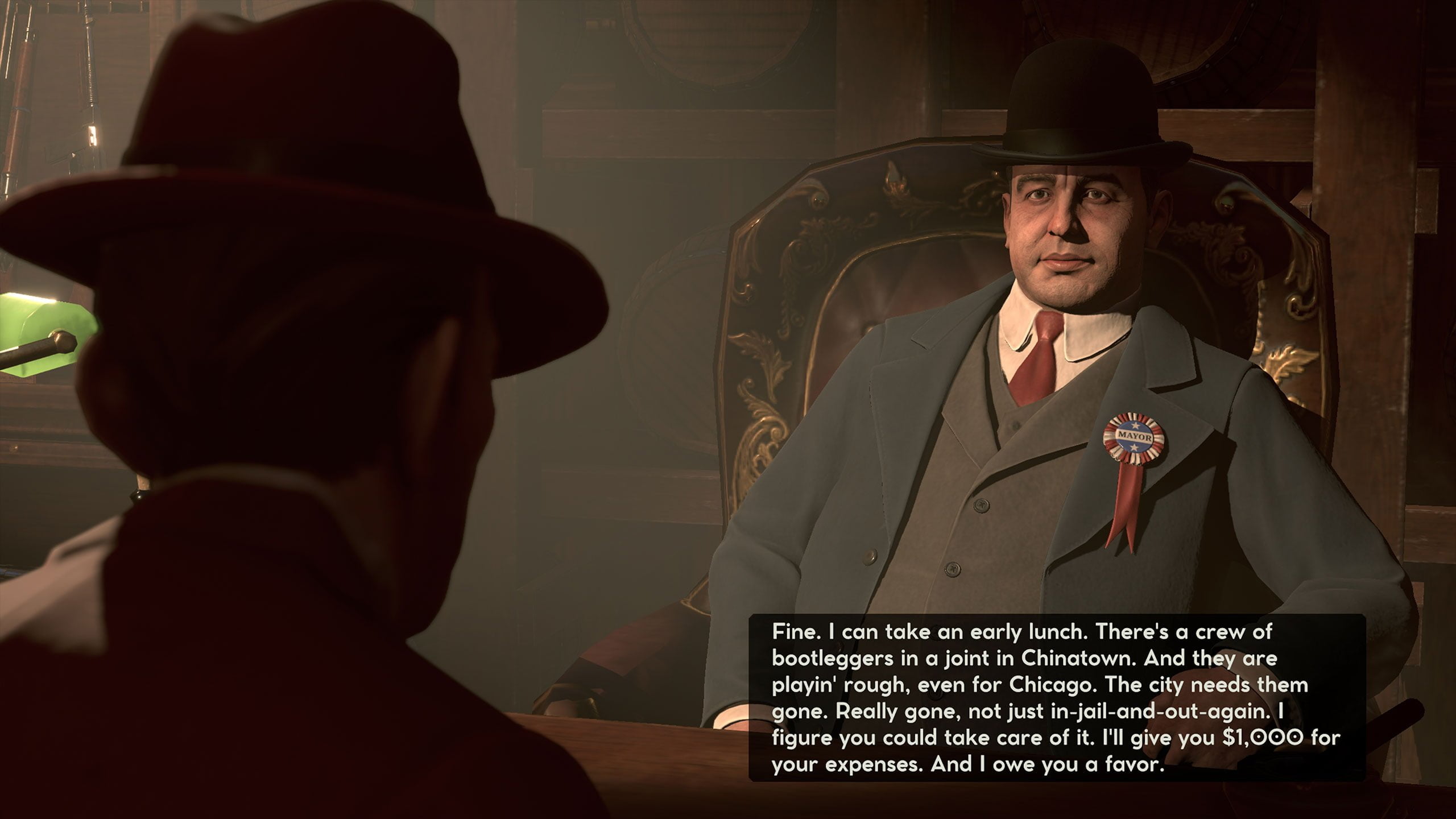

Another tool the game offers to help players mark their mark on Chicago, and to create their own narrative, is the interactions with other factions. When exploring the city’s ten districts – which can be done in a detailed close-up view or on an abstracted strategic map – the player’s boss will run into representatives of rival factions. Should your boss stumble into some wiseguys employed by Al Capone, they will likely be invited to a sitdown. In theory, this is where game-changing deals can be carved out, mano a mano, but in practice players are likely to come away with a 4% discount on brothel ambience upgrades. These paltry rewards make engaging in diplomacy feel like a waste of time, and undermine the game’s atmosphere.

At first, managing rackets is engaging but as time goes on and bosses acquire dozens of establishments, it becomes more and more difficult to justify the time needed to upgrade and maintain this sprawling network. Through this accumulation of busywork, Empire of Sin gives players a perverse incentive to instead arm themselves, provoke wars, and eliminate rivals more quickly. In effect, this shortcuts much of the game – once the other factions are crushed, the city falls into the player’s control and the game is over. The abundance of bugs – some fixed in a day one patch, others not – also encouraging skipping ahead.

Empire of Sin focuses on a uniquely fascinating time and place in American history, and often does a good job in recreating the pleasures and dangers of 1920s Chicago. Somewhere within its maze of systems is the potential for a great gangster game, but Romero Games have poured so much content into the project and stretched the design so thin that none of its component parts are truly compelling. The wait for a definitive mob experience goes on.