Everything has led to this moment. The Devil’s Basilisk – the London police department’s most advanced AI system – lay before me. After countless heists and meticulous planning, I’d finally reached the end with 27 days to spare. I hack the Basilisk’s last layer of security, grab the metal heart from its housing, and make my escape.

But of course, as with all good heists, things go awry. I’m halfway to the escape pod when I’m suddenly besieged by cops in hovercrafts equipped with Gatling guns. They tear through the bricks of the police station as I frantically run for the exit, barely avoiding their fire. But it’s no use. As soon as I exit the building, one of the bullets hits me and I go down instantly. So close! If I’d just deployed my smokescreen, maybe I’d have gotten away safely. Or perhaps I needed a better escape route.

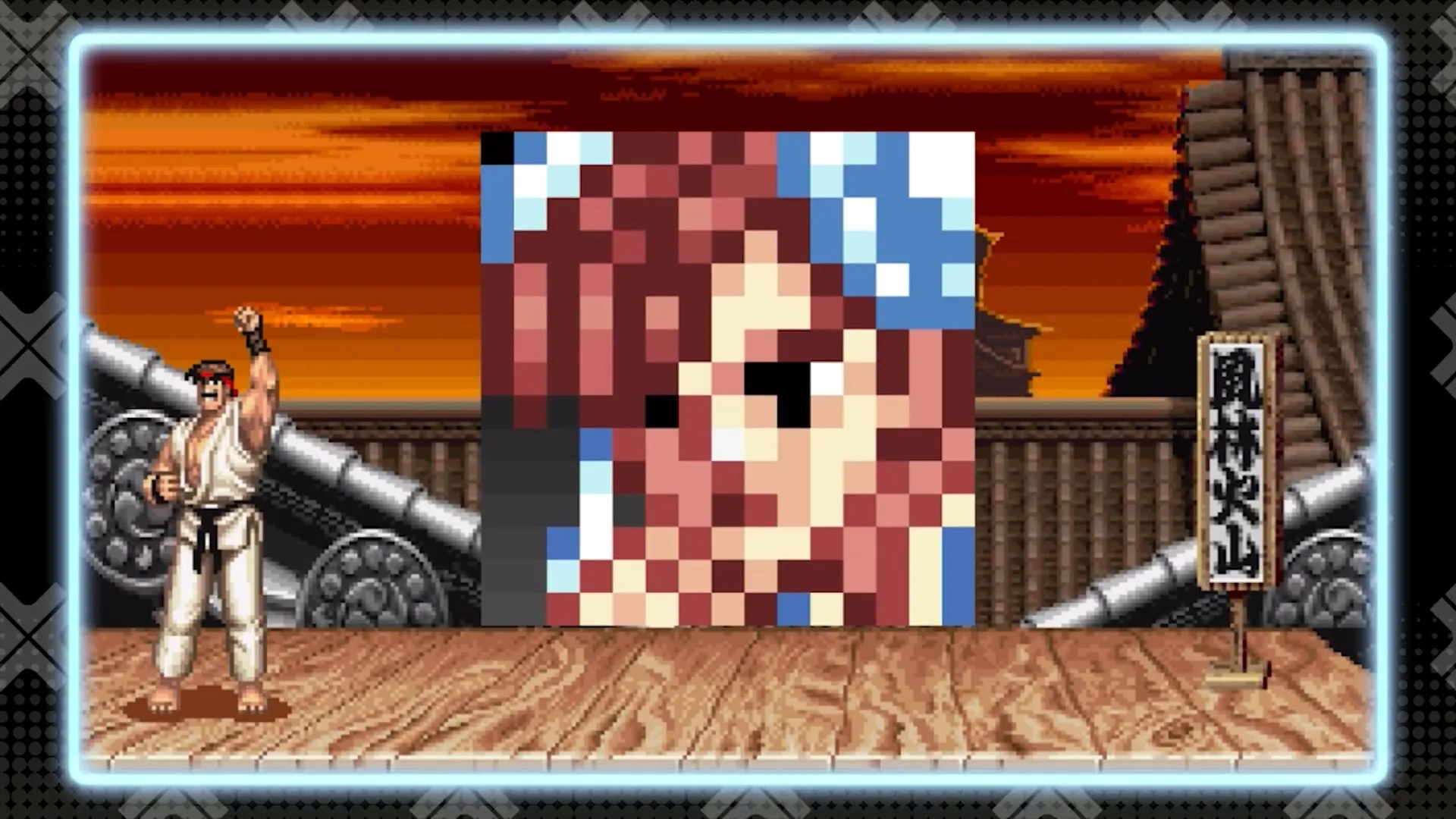

The Swindle is a procedurally generated heist game from Size Five Games. Set in a steampunk version of London, the premise is that Scotland Yard is a 100 days out from launching their new advanced AI system, The Devil’s Basilisk, which is set to spell the end for crime all throughout the city. As a thief yourself, you cannot let that happen. Over the course of the next 100 days, you pull off heists across a handful of locations, gathering cash to buy tools and upgrades to prepare yourself for the final job. A hundred days is more than ample. Plenty of time to prepare, and plenty of leeway should you fail a few heists. Whether or not you succeed, however, is mostly up to the level.

The Swindle’s use of procedural generation generally creates levels that can always be completed with whatever your current toolset is. The Slums – the first environment – don’t have much in the way of high-tech security measures, for instance, so you needn’t worry about buying second-tier upgrades – triple and quadruple jumps, hacking doors and security stations, smokescreens, etc. – to take on heists there. Whereas the Warehouse District is rife with such measures, making it all but impossible to turn a profit there without the skill to hack doors and security stations. It creates a steady difficulty curve, pushing you to buy new upgrades just before the need for them arises.

Tools in particular are especially important. Bombs allow you to forge your own path or entry point, as well as destroy traps or cameras. The EMP disables any security bots or drones in your immediate vicinity, but also any computers (I think; didn’t test it enough to know for sure). The remote detonator can set off mines and EMPs from a far, thus turning them into weapons of your own. Smokescreens allow you to pass through an enemy’s line of sight unseen and can be upgraded to automatically deploy upon capture. Bugs can be installed on computers to continue siphoning cash from them even after you’re long gone from that area. And goggles can bought and upgraded to point out locations of computers, security stations, as well as show how much noise you’re making and how far it travels. Alone, any of these tools doesn’t achieve a whole lot. Together, they can make a heist considerably more manageable. Even so, success still remains dependent on the level itself.

A successful heist, at the bare minimum, involves hacking all the computers in the area. They’re key targets because you get a ton more money out of them than you do by bagging stray stacks of bills and sacks of pounds. Ideally, a successful heist involves sweeping the level for all the cash it holds without raising an alarm, maybe throwing down a few bugs to siphon more funds. The former scenario is generally easy to pull off. Hacking whatever computers you can and making your escape is safer and still highly profitable. By pulling off a completely successful heist, however, particularly with the same operative numerous times, multiplies your earnings considerably.

That’s where things get tricky. You’re incentivized to pull off successful heists in succession since it earns you more money, which in turn allows you to buy upgrades earlier, thus giving you more time to take on the final job. It’s a big part why dying is so crushing. Because you’re often not just losing whatever cash you bagged from the level, but the multiplier you’ve built up over several heists. During the early goings especially, when you’re only earning hundreds of pounds at a time, such losses are devastating.

It’s important to make money fast, because doing so allows you to outpace the difficulty curve. Rather than merely lock new enemies and traps to each district, The Swindle introduces them piecemeal over time as the days pass. In the first ten days, for instance, The Slums go from being guarded by basic security bots with limited vision cones to being armed with drones, mines, and bots with larger vision cones. Other districts don’t have that same sort of progression – at least not in any obvious ways. It definitely felt like it was there, as heists would steadily become harder over time. The longer I spent pilfering cash from the Casino District, the harder it became. Stronger, more vigilant bots would appear with greater frequency as traps became increasingly more common. Granted, this was all probably hard-coded progression, but it felt like a result of not moving fast enough. That taking so long to steal the Devil’s Basilisk allowed the police to develop harsher security measures.

It’s why I often started over after failing too many consecutive heists. I felt pressured to move quickly because the steady introduction of new security measures in the first ten days conditioned me to believe that the difficulty scaled with the passage of time. If I lost too many heists, I was convinced I wasn’t going to be able to properly handle whatever the game would throw at me next, that I wouldn’t be able to make enough cash to unlock the next district, let alone the final job. None of that was true, of course – so long as you’ve got time left, you can always turn things around – but in the moment, it didn’t feel that way.

The Swindle is designed around multiple playthroughs, specifically in the same way a roguelikes are. Success comes from learning through failure. Every death and mistake is a lesson in how to be a better thief, every new game allowing you to streamline the upgrade process as you come to learn what to prioritize and when. The difference is that failure is long and sustained instead of quickly shrugged off, which makes losing the game entirely utterly devastating. But that’s also what makes playing The Swindle so satisfying. The lows of failure may be crushing, but the highs of success are incredible.

Prowling around buildings, sizing them up and planning your route, breaking in, bagging the cash, and escaping never ceases to entertain, but it’s the challenge that makes The Swindle shine. Because the odds are so stacked against you, finishing the game feels like an actual accomplishment. It’s not merely satisfying, but exhilarating. The Swindle can be harsh sometimes, but it’s hard to imagine how the game could be the same without it.