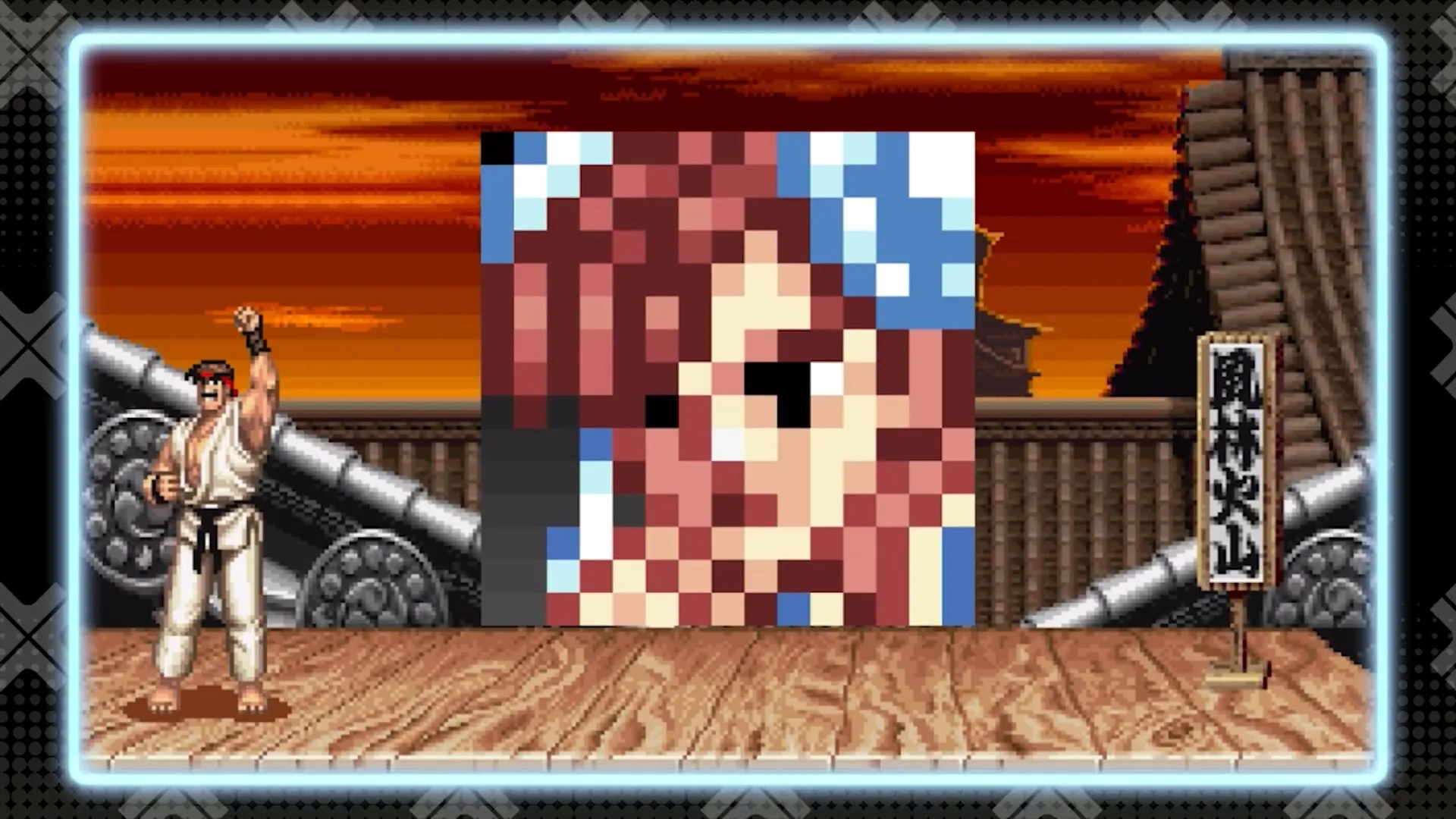

Klaus begins on a familiar note. A man wakes in a basement with no memory of who he is or how he got there. The name “Klaus” is written on his arm, which he assumes must be his name. You then go on to guide him through several floors of levels, working your way through puzzles to reach the exit and maybe figure out what’s going on. It looks to be a standard story about amnesia wrapped in a rudimentary puzzler platformer package, at first, which holds true to for the first several levels. But it soon reveals itself to be far more complex and clever.

The story revolves around Klaus’ growing identity crisis as he learns the truth about himself. The major beats are explored as you naturally progress, largely through Klaus’ commentary that’s plastered on the walls, but the finer details are locked behind memories scattered about each level. These memories grant a clearer understanding of the narrative, providing a glimpse at the events that led up to where the game began, at what kind of person Klaus was. They’re more supplementary to the narrative at large, having little bearing on the proceedings, but they’re well worth seeking out.

You make your way through the building contending with a bunch of rudimentary jumping puzzles to reach the exit. Spike pits, moving platforms – you know, the usual. Klaus does make them a touch more interesting, however, by placing you in control of some of these platforms. By using the touch pad, you can move a cursor around to gain direct control over certain objects with the right analog stick. This primarily consists of moving and twisting platforms as necessary to allow Klaus to progress, but occasionally you have to use them to transport keys or dispatch foes.

On paper, it doesn’t sound particularly noteworthy. But it’s the way it’s incorporated into the fiction that makes it interesting. Klaus cannot move of his own volition and you don’t actually have direct control over him, like you would in a traditional videogame, because you’re not playing as him. You’re merely someone else watching from afar, the person Klaus refers to as “the player.” It’s not merely some fourth-wall breaking shtick – they’re an actual character in the game, the one you embody. The touchpad interactions are the only means you have to affect the space directly instead of through someone else.

It’s made especially apparent when Klaus breaks free of your control for a few levels. Due to a revelation half-way through the game, he doesn’t trust you anymore. He’s had enough of taking orders and decides to take his life into his own hands. You can’t forcefully retake control and stop him – he has to willingly hand it over. Thus you keep him alive by manipulating doors and platforms so that he doesn’t run into danger, as he’ll gladly keep throwing himself in harm’s way. With the touchpad being your only form of input, these sequences drive home just how detached you are from the events on-screen, how little control you actually have, and how much of that control is built on trust. You’re partnership is built on both of you working toward a common goal: figuring out what this place is and how to escape. But since your avatar can’t talk, Klaus has to trust that your goals align with his. When he believes that’s not the case anymore, Klaus doesn’t trust you and acts of own volition. When he does trust you, he willingly cooperates.

It’s an interesting twist on how videogames usually acknowledge videogame conventions. Klaus doesn’t play it all off for laughs or break the fourth-wall in the process and instead plays it straight throughout, actively works it into the fiction and justifies it. Developer La Cosa Entertainment could have easily settled for explaining the touchpad functionality as some strange ability innate to Klaus, but instead they chose to explore it through the lens of the narrative. It results in a much stronger and intriguing story, as well as a fascinating interpretation of the relationship between the player and character.

Eventually Klaus get a partner by the name of K1. Where Klaus is small and agile, K1 is large and powerful. He provides the strength to break down barriers and throw Klaus to spaces he otherwise couldn’t reach. He can also glide. The game hits its stride here, building its levels around using the two characters in tandem. It takes some adjustment to get used to controlling two characters after spending the entire first chapter of the game with only Klaus, especially as the early stages with K1 don’t make strong use of their individual strengths.

The game’s at its most inventive during the memory sequences. The challenges they throw at you differ greatly from those in the main game. Some make you big and slow or shrink you to run at lightning speeds, for example, while others have you running inside the walls or moving lights to reveal hidden obstacles. These levels embody Klaus at its best, demonstrating a degree of creativity not found in the rest of the game. It’s a shame that the ideas explored in these segments aren’t used elsewhere, but given their increased difficulty, it’s easy to see why.

Klaus isn’t without faults, though. It’s not always clear how much momentum you need to clear certain gaps or reach certain ledges, nor is it clear how long you have to press the button to gain maximum height. It’s a tad annoying when you miss a ledge because you didn’t get enough of a running start, but infuriating when you fall into a pit of spikes for the umpteenth time because you’re just slightly off for not holding the jump button down for half a second longer.

The momentum is also troublesome with springboards. You don’t have much control over Klaus and K1 when they bounce off one, which can make moving through hallways that must be crossed by keeping your jumps in line with a moving springboard an exercise in frustration. Double-jumps are the only way to correct Klaus’ trajectory, but more often than not that leads to him missing the board entirely. K1 at least can just glide back down, making it a non-issue for him, but he also seldom deals with those.

Still, even in spite of those annoyances, Klaus’ platforming remains enjoyable. Running through obstacle-laden corridors jumping over spikes and avoiding saw blades in one smooth motion never gets old. Most of the platforming takes a more methodical approach, asking you to take your time and move carefully than to dash through it recklessly, but the moments where it allows – or even requires you to let loose demonstrate how tight the traversal can be. The memory sequences are a good example of this as several of them demand speed and precision.

As developer La Cosa Entertainment’s first project, Klaus is a strong debut. The way it uses videogame conventions as part of its story is inventive and clever, turning an otherwise rudimentary puzzle platformer into something far more intriguing. Curious to see what La Cosa does next.