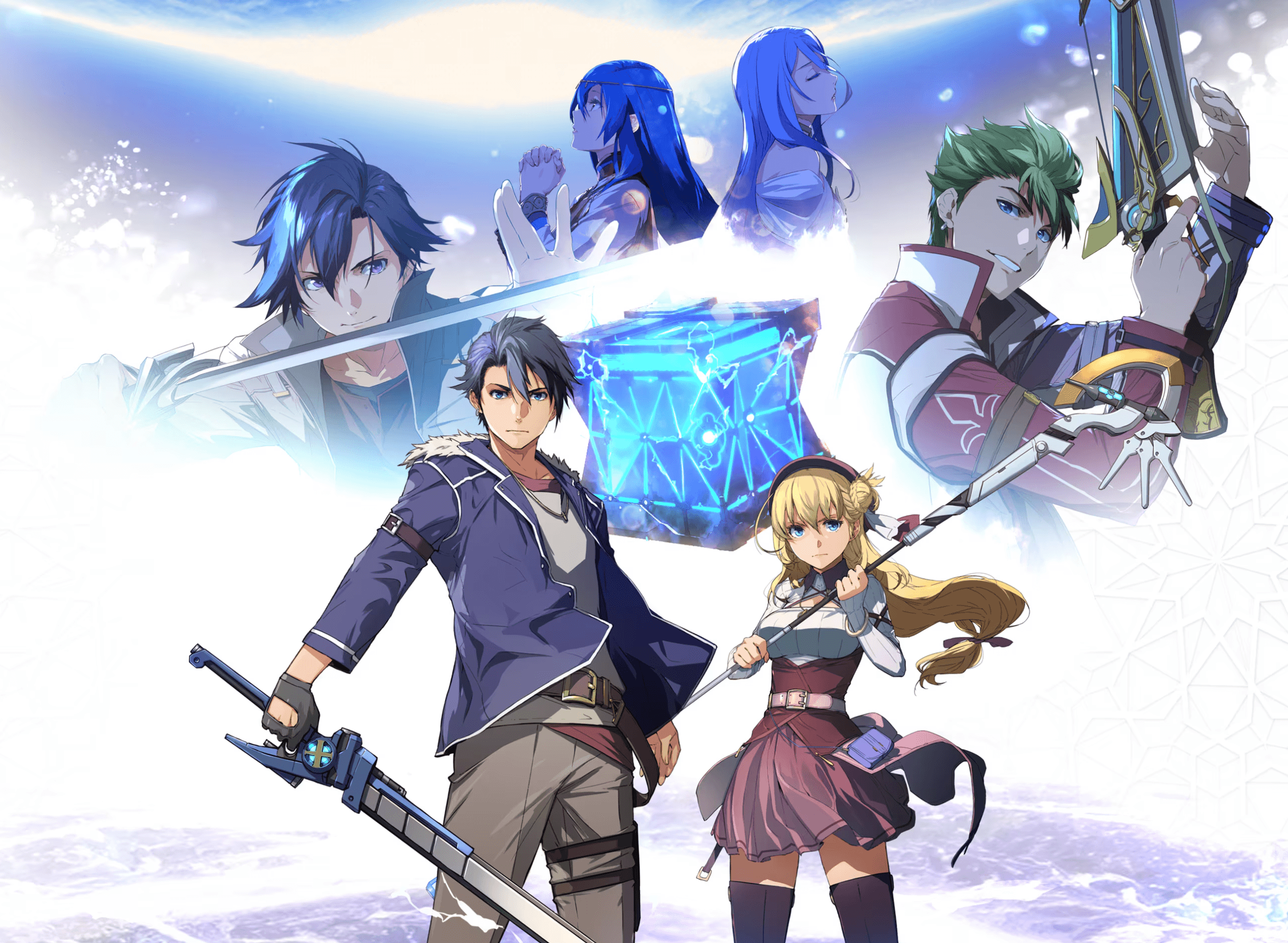

Developed in Brazil by indie studio Glitch Factory, No Place for Bravery is a 2D action game which fuses Soulslike combat with a Metroidvania structure. While this mix is competently executed and the decaying fantasy environments are attractive, the game offers little that is new. Too often, No Place for Bravery delivers frustrating fights and repetitive trap runs instead of the story it is trying to tell.

The setting is the fantasy world of Dewr, which has long since fallen on hard times. Players take on the role of Thorn, an ageing former warrior who has hung up his weapons to run a tavern. Despite finding some solace with his wife and an adopted son named Phid, the old soldier is haunted by the disappearance of his daughter Leaf years earlier. The plot of No Place for Bravery is kicked off by Thorn learning that Leaf may still be alive somewhere. The game has a few story-defining choices to make and, oddly, one option is to forget about Leaf altogether. This results in Thorn staying at home, and the game ends abruptly about an hour in.

Of course, this potentially emotive “conclusion” is undercut by the fact that the player will inevitably reload and take the other path – the one that leads to the rest of the game. Thorn sets off into the world, carrying Phid – who is unable to walk – with him. Progressing through Dewr means visiting and revisiting a series of locations visible from the outset on a world map. Access to certain locales is gear-gated – for example, Thorn can’t bypass crumbling stone walls before acquiring a giant hammer to smash them.

Despite the game’s narrative ambitions, which are apparently rooted in the real-life experiences of the developers, the core of No Place for Bravery is actually its combat. This will be familiar to any veteran of FromSoftware’s work, or of its growing list of derivatives. The enemies that wander Dewr hit hard, and their attacks must be learned. Thorn’s own attacks, standard and special alike, draw on a limited but quickly recharging pool of stamina. Characters deprived of stamina become extremely vulnerable for a short time.

To a limited extent, Thorn’s abilities do progress over the course of the game but despite the marketing, No Place for Bravery can’t be called an RPG. Defeating enemies earns Thorn coins, which can be spent at campfires to unlock new abilities tied to specific weapons. This system is confusing at first, because some coins are lost on death and new skills also require certain loot drops which can’t be found in the early game. Also confusing is the meaningless names of most inventory items, which often come in several slightly different variants – it’s often difficult to tell which healing item to use, for example.

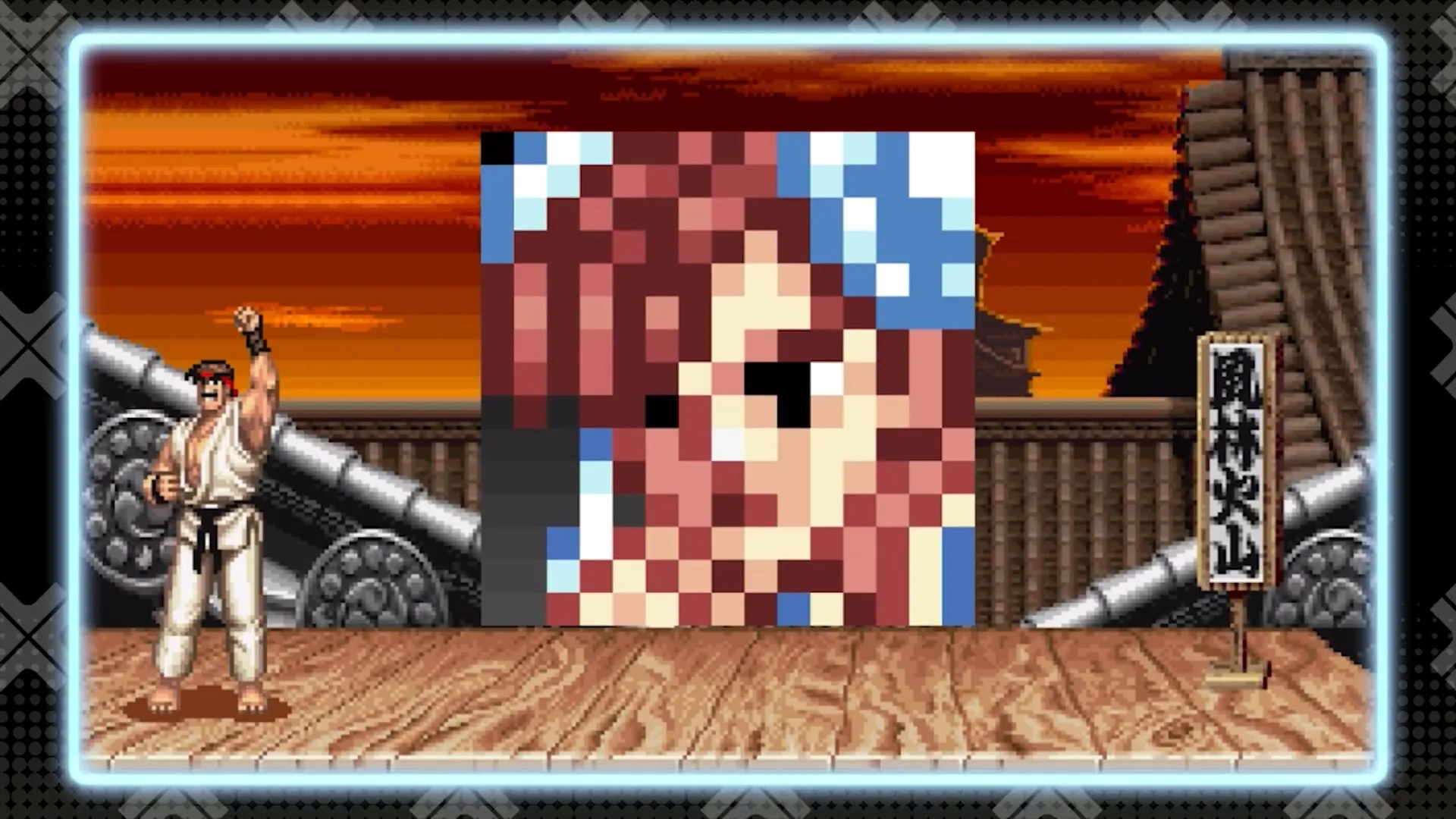

Design decisions like this, which frankly can feel obnoxious, are unfortunately quite common in No Place for Bravery. The game has no real pause function, something which should be strongly discouraged. Many locations are also laden with instant-death pits, flame traps, and other obstacles which were better left in the designs of the 1990s – or at least in a game with a proper jump function. Completing these sections once is bad enough, but they sometimes need to be tackled repeatedly for no good reason and it wears very thin indeed. At times, the camera will zoom out to help players survey a wider context but this can often be fatal because it makes characters appear tiny and Thorn and his enemies become difficult to tell apart.

These mis-steps are frustrating partly because the strengths of No Place for Bravery are very real. The aesthetics of the game are quite accomplished. Animations are particularly impressive, and clearly the product of a lot of effort. Grass sways as Thorn passes by, downed enemies tremble as they wait to be finished off, and Phid shifts position as his father swings a hammer or a sword. The combat won’t be to everyone’s taste but can become an elegant and deadly dance.

Ultimately though, No Place for Bravery is so heavily indebted to its influences that it never carves out a real identity of its own. A game that should lean heavily on its combat, and on telling its story, instead becomes bogged down with frustrating traps and repeatedly going over the same ground. The reliance on opaque systems and too many written lore extracts also detracts from the accomplished visuals and sound. In a market increasingly crowded with games drawing from the same well, it isn’t clear that there is a place for No Place for Bravery.