Fighting games can be (very) loosely split into two groups: those that are more reserved and “honest,” and those that go completely buck wild and often have some real bullshit (in an endearing way) to deal with. DNF Duel falls into the latter category.

DNF Duel is wild. Based on the popular MMO Dungeon Fighter Online, DNF Duel is the latest fighting game from Arc System Works and Eighting, best known for their work on Marvel vs. Capcom 3, which, if you’ve ever seen in action, should give you an idea what kind of absurdity to expect here. Each of the game’s 16 characters have moves that cover most of the screen and can convert most hits into devastating combos. It is a game that favors unrelenting offense and rewards it in kind, requiring an equally active defense to withstand. DNF Duel is a game that encourages active play to the point where merely blocking won’t save you for long. It is fast and lethal, a couple mistakes being all it takes to lose a round against the wrong opponent.

But it is also a game that seeks to follow current trends toward reducing execution and system complexity in favor of approachability. Granted, that’s a goal many fighting games strive to achieve in recent years. In a genre that has, intentionally or not, become one rife with high execution requirements and a steep learning curve, trying to satisfy the competitive needs and interests of the community while still being beginner friendly (that is, lower the execution barriers enough to allow casual fans of the genre to do all the cool stuff without first spending hours practicing) is a difficult task. DNF Duel attempts to tackle this a couple of ways.

First and foremost is by reducing input complexity. Like Granblue Fantasy: Versus, DNF Duel tries to simplify inputs by letting you use a single button and a direction for every move in the game. So instead of having to do a quarter-circle forward or back motion to throw out an attack, you can just hold forward and press the button instead (the option to use traditional inputs still exists, of course). Think of it like how Super Smash Bros (and platform fighters broadly) handles its specials. This means all of your special attacks are just a button press away, including reversals (moves that have some amount of invincibility to allow you to interrupt your opponent’s assault). The game does account for this, however, by limiting their window of invincibility greatly to avoid making them too powerful.

This is on top of it being a four-button game that follows the standard method of chaining attacks together – light > medium > heavy (called “skills,” in this game) > specials (or “magic skills”) – which makes it easy to chain together simple combos that look as flashy as they are damaging. The actual execution for stronger combos is difficult, of course (fair amount of tight windows to chain attacks – expected – and some micro-dashing and here and there, which; ugh), but I’ve mostly gotten by without learning the “optimal” routes.

On a systems level, it’s relatively straightforward. It’s not a mechanically dense game, but the ways its mechanics work give it a fair amount of room to work with. You begin every round with 100 magic points to start, which quickly regenerates over time. These dictate whether you can use magic skills. As long as you have any amount of magic points – even just one! – you can use them. If you run out, however, you’re briefly put into an “exhausted” state wherein you’re locked out of those skills while you wait a bit for your magic points to start recharging. The consequences of falling into that state are obvious – limits your offense and especially your defense if you don’t have any magic available – but it regenerates fast enough that you’re often not stuck waiting for it to refill before you can do anything. If anything, the game encourages you to be fast and loose with spending it.

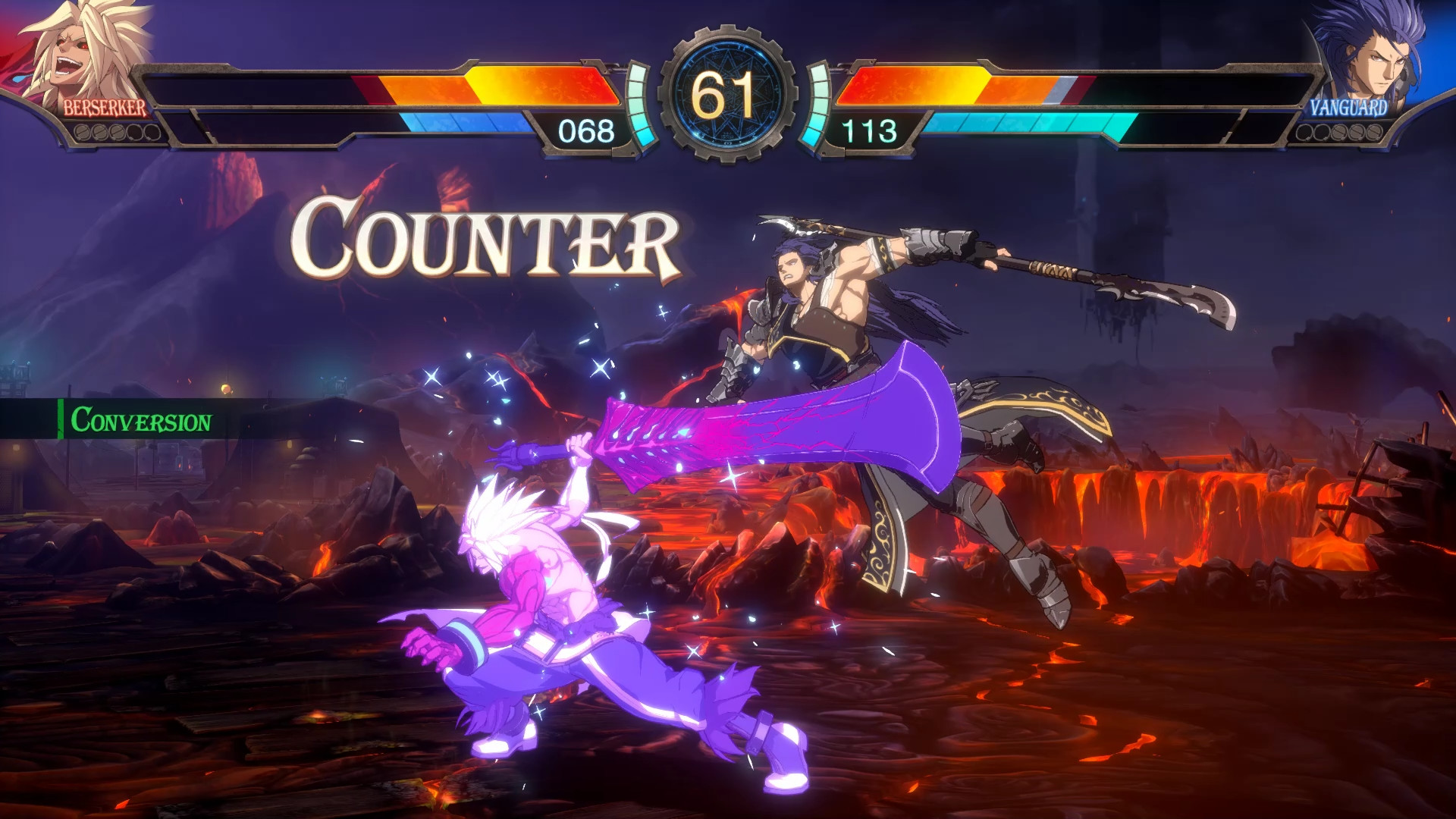

Making the most of whatever resources you have available feels like the play in DNF Duel because you want to keep your opponent locked down for as long as possible. Where blocking in most fighting games is the safest thing you can do, DNF Duel makes it a limited resource of sorts. The “guard meter” is a bar that slowly depletes with each attack you block. Take enough damage and you become “guard broken,” which leaves you wide open for a direct hit. You’re forced then to find and exploit any gaps in their offense and make the most of it. Whether that’s by mashing a fast attack, using your reversal, dodging forward to escape their pressure, or spending magic points on “guard counter” (essentially another reversal, except it does no damage and knocks the opponent way back), DNF Duel wants you to do something.

The guard meter exists to discourage passivity. Arc System Works fighting games often have some kind of mechanic in place to punish such play. Theirs are games that do not want you to avoid engaging your opponent. Where their usual solution ends in putting you at a disadvantage, however (emptying whatever meter you’ve built up, effectively removing a defense mechanic, or increasing damage taken, to name a few examples), DNF Duel actively encourages interaction. By making blocking have a material cost beyond chip damage, players are forced to adopt a very aggressive play style. If you have your opponent cornered, then it’s in your best interest to throw literally everything you have at them to deplete their guard meter as quickly as possible. Likewise, if you’re the one being cornered, you have to try countering their offense since you can’t just wait for them to overextend to take your shot.

A tight offense might run down the opponent’s guard meter, but that means they can just guard counter easily since they can count on still being in blockstun long enough for it to work and send you flying. So you’re still encouraged to try and stagger your button presses to bait them into mashing a button or using a reversal only for it to be blocked. But at same time, by doing that, you open yourself up to the opponent being able to dodge past you entirely and thereby gain some much needed space. And of course, throws can bypass guarding entirely, so that’s always a threat as well. All fighting games play around these basic ideas and the mind games therein, but DNF Duel hastens the pace at which these interactions play out because of the guard meter’s existence. It forces both players to act quickly because blocking doesn’t provide the same sort of safety you’d get in most other fighting games.

This is further compounded by the game’s approach to neutral. DNF Duel is a very ground-focused game. Only two characters have any sort of aerial movement, which even then is limited. The game also doesn’t allow you to block in the air at all, making jumping an extremely risky choice. Given that everyone has at least one or two moves that cover a good portion of the screen, the vertical space included, you can’t really make avoiding your opponent the play. It instead becomes a constant volley of projectiles and generally big attacks being thrown at each other until someone gets a hit or whiffs big time to let the other player run in and start laying on the pressure. There’s certainly room for a patient approach, but in my experience, it almost always goes straight into all-out offense instead.

To compensate, the game tries to make up for damage dealt by making you stronger over time. As you take damage, your MP bar grows, maxing out at 200, expanding your options at any given moment. Once your health is at 30% or lower, you also enter an “awakened” state that activates a unique character trait (faster MP regen, increased damage, inflicting various debuffs on the opponent on hit, etc.). For some characters especially, their awakening skills allow them to make frightening comebacks if they know what they’re doing. It all contributes to the game’s focus on being unrelentingly aggressive.

Taking damage also opens up one of the game’s more unique mechanics in “conversion.” Conversion is essentially like Chain Shift from Under Night In-Birth or Roman Cancels from Guilty Gear in that it allows you to immediately cancel any action to reduce recovery and continue pressure or open up new combo routes, as well as quickly refill your MP. The main difference is in the conditions you have to meet to use it. Conversion is only available when you have “white health,” which is gained from taking damage from attacks directly or while blocking (known as “chip damage”), as conversion uses that health to activate it. The trade-off is that white health slowly regenerates over time as long as it remains, so you can choose to try and let that health regenerate so you can take more hits in the long term instead. If you take a hit from a magic skill, however, all that white health is permanently removed, effectively making it an extremely limited situational resource.

Spending health in exchange to refill your magic points and the potential to extend combos or block pressure is an interesting idea. It’s hard to know how much it influences strategy at this point, however, given how it’s only readily available to two characters (Berserker and Trouble Shooter) who have moves that cost health in exchange for buffs, whereas the rest of the cast has to wait to use it, if at all. It’s early days still, so I imagine it’ll come into play more over time, but right now it feels more like a concept that’s better on paper than in execution.

The tutorial for all this is… passable. It’s in line with most other recent Arc System Works fighting games in that it covers the basics and broad systems well enough to get you acquainted with everything, but doesn’t really dive into specifics the same way other games like Under Night do. The character specific entries are just good enough to provide some context for what each character does broadly, and the combo trials seem to provide an okay starting point for understanding combo theory. The challenges, which put you in specific situations the game asks you to find solutions for (anti-airing an opponent who is jumping in, for example, or getting past someone pelting you with projectiles from the other side of the screen) are a standout for how they provide tips geared toward your choice of character. It’s a decent way to get new players to think about dealing with common situations and familiarize them with their character’s options, but it’s hardly enough to make up for how paltry the overall tutorial feels compared to its contemporaries. I’ve already said my piece on the matter when reviewing Guilty Gear Strive last year, and the same still holds true here. (Long and short of it is it’s easier to learn a game when the developers provide a strong basis to work from in-game rather than offload that work entirely on the community.)

Like most other modern fighting games, DNF Duel uses rollback to ensure online play is smooth and stable. For the grand majority of the games I’ve played, including against opponents on the other side of the globe from where I am, it’s been great. The only issue I’ve had is that sometimes the first game of a set will be a bit choppy, but it always resolves itself after the first match. This has only happened when I’m playing across vast distances, but even then, it seems pretty rare with regard to how often it happens since I’ve had plenty of other sets against people all over and not had that issue, so… something to look out for.

It’s hard to know what DNF Duel will look like in a year’s time, let alone a few months. Fighting games get huge updates so frequently these days it’s impossible to know what form they’ll take in the long term, whether due to the developers deciding to make massive changes or the meta shifting in such a way that pigeon-holes the greater play dynamics. Right now, though, it’s a ton of fun and relatively easy to hop in and just start pressing buttons. Hopefully it can stay that way for a while because it’s nice to have something to just turn on and get some quick sets in without feeling like I need to actually put in actual work to do anything.