The beloved Alien series has always been a good fit for videogames, and playable adaptations now hugely outnumber the films themselves. With its greater emphasis on action, James Cameron’s 1986 masterpiece Aliens is the entry most suited to the form, but has led to a decidedly mixed crop of releases. Since the first timely tie-ins on the ZX Spectrum and the Commodore 64, Aliens games have racked up a nearly 40-year history. With Aliens: Dark Descent, the French studio Tindalos Interactive has finally captured the film’s unique feel in the form of a genuinely novel tactics game.

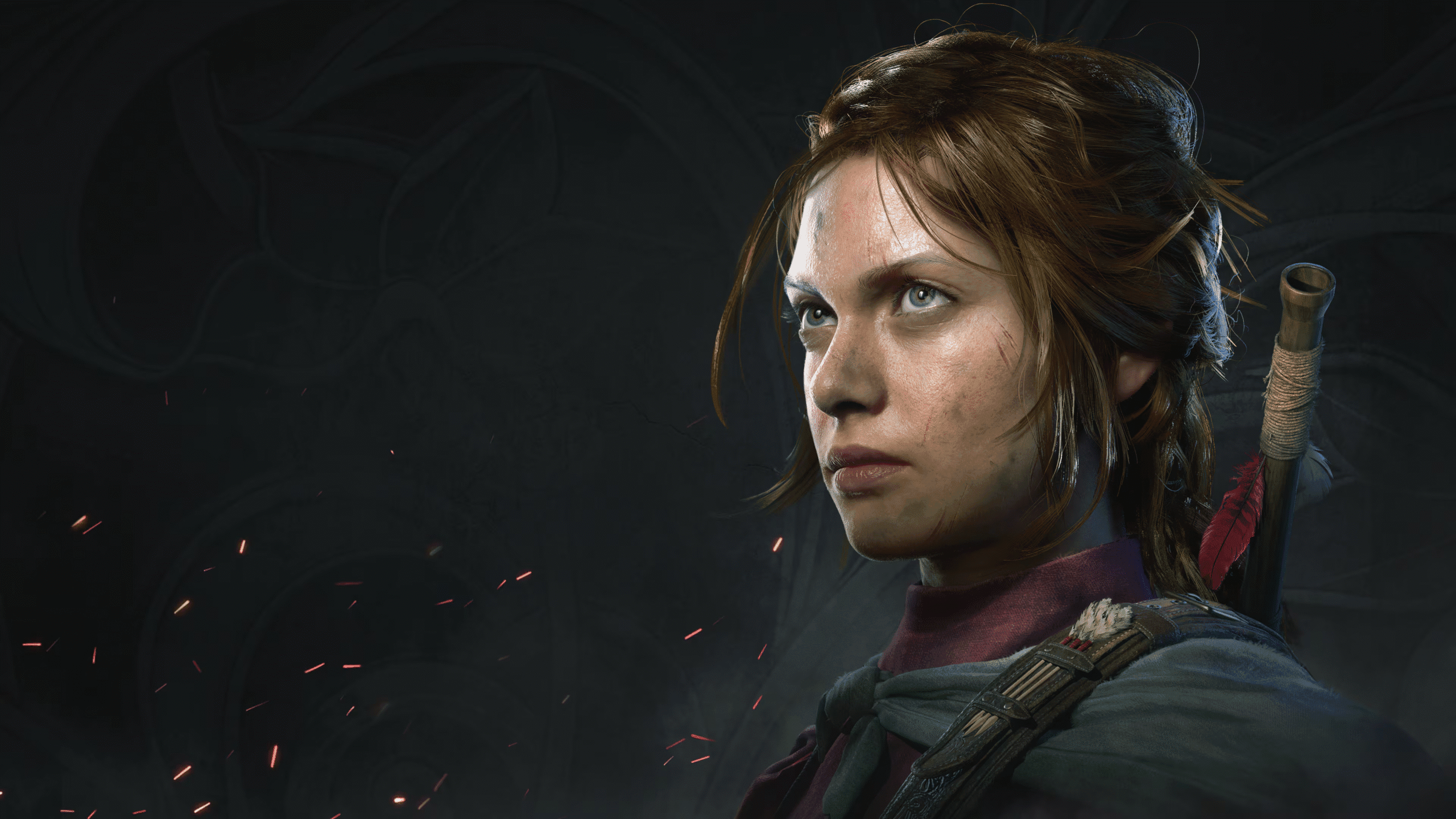

Alien-related games tend to aim to carve out some narrative distance from the films, and so it is with Aliens: Dark Descent. It is set some time after the events of Alien 3, in the year 2198. The harsh planet of Lethe has been sparsely colonised for mining and research purposes by the Weyland-Yutani Corporation. When a xenomorph threat emerges on the orbiting Pioneer space station, Deputy Administrator Maeko Hayes is forced to step up. She becomes the game’s central character, working with Colonial Marines aboard the USS Otago to contain the infestation.

In story terms, Aliens: Dark Descent lifts liberally from Aliens and from the wider corpus of books and comics in the franchise. Hayes is comparable to Ellen Ripley, and her military opposite number Jonas Harper resembles Corporal Hicks in some ways. Weyland-Yutani is as secretive and malign as ever, and there are malfunctioning androids, a deranged cult, and all the gloopy xeno-violence you can shake a pulse rifle at. Tindalos have crafted a fairly compelling story, which given its extended length and episodic structure brings to mind an Aliens TV series. Where the game truly impresses, though, is how its gameplay captures the distinct Aliens vibe.

Attempting to survive and counter the infestation means sending squads of four (and later five) marines to various locations in orbit, and on the surface of Lethe. Missions are not turn-based, but take place in real time, which is critical to the maintenance of tension. A game like Hard West II throws deadly threats at players, but also provides them with ample time to think. Not so in Aliens: Dark Descent – fending off an alien assault means making snap decisions, and often enduring outcomes that are less than ideal. Critically, the squad is controlled as a unit – not as a group of individuals. Specific tasks are assigned by the game to particular marines, based on their skills, gear, condition, and location.

Another unusual but clever decision Tindalos have made is crafting sprawling missions which can rarely be tackled in a single deployment. Instead, troops from the Otago will revisit the same refinery, mine, or habitat multiple times to gradually chip away at objectives. These deployments are persistent, with lasting consequences. Forced to leave a damaged sentry gun behind? It may be possible to repair and recover it on a later visit.

It is often prudent to cut deployments short, because of the intensity of the battles and the ruinous effect of mental stress on troop effectiveness. The presence of enemies on the squad’s motion tracker causes stress levels to rise, and these can only be lowered using combat drugs to calm troops down or tools to seal them into safe rooms for a much-needed rest. Both of these resources are scarce, and so Dark Descent constantly imposes tough and exciting decisions.

Wherever possible, players will want to keep the squad undetected. This can be done with smart movement or by using the sniper rifle possessed by the scout class, which can be upgraded with a suppressor. Eliminating xenomorph sentries in this way gives the squad some breathing room, but certain mandatory actions are sure to alert the hive. The battles in Aliens: Dark Descent are breathless, nervy, and gripping affairs. Sentry guns, mines, suppressive fire, and other key abilities have to be used with speed and care in order to tackle the more determined assaults and prevent catastrophic losses.

The use of abilities is the one deviation from real-time play during missions; opening the ability menu slows time, or provides a full pause on lower difficulties. The Otago’s troops never feel invincible – over the course of the 12 missions, players are sure to lose valued soldiers, and see others lose limbs or gain debilitating mental traumas. It is more difficult to really connect with these grunts than in, say, XCOM 2, but they do develop satisfyingly over the duration of their ordeal. Some of the most memorable moments in Aliens: Dark Descent are the emergent ones – desperate efforts to evacuate a valuable, unconscious soldier from a bungled operation while the xenomorphs are closing in.

Conversely, one weakness of the game is that situations can go so catastrophically wrong so quickly – especially during setpiece, story-oriented battles – that players will want to reload rather than live with the consequences of their mistakes. While it is difficult to see how the developers could have prevented this, it can undermine the game’s otherwise superb tension.

Between tactical missions, there is also a strategic layer reminiscent of XCOM 2, but somewhat simpler. On board the Otago, players can develop new weapons, train rookie marines, and acquire new passive buffs based on recovered samples of xenomorph tissue. Rather than particularly engaging strategic decisions, these segments primarily offer a welcome break from the almost unrelenting tension of the tactical missions.

In many ways, Tindalos Interactive have done a superb job with Aliens: Dark Descent. The game succeeds where previous efforts have failed – to capture the unique aesthetic, sound, and intensity of Aliens. This is a compelling tactics experience which takes inspiration from other games in the genre, and yet which feels genuinely unique and novel. Over time, the strong stigma once associated with licensed games has begun to wane; Aliens: Dark Descent is an excellent extension of its franchise and a thrilling challenge in its own right.